ESOP Is Central to Startup Competitiveness

With several renowned startup hubs in Germany and a growing number of exits, the country has plenty of reasons to feel good about its progress in the tech / digital economy. There have been newsworthy funding rounds in the past decade, granting $1 billion unicorn status to startups like N26, GetYourGuide, and TeamViewer, which recently pulled off the biggest stock market listing in Europe. Even though Germany is home to only twelve unicorns – in comparison with twice as many in the UK (a smaller country in terms of GDP) – the country is leading in many sub-industries such as open source software and still has many significant exit valuations ranging between $20 and $150 million. While it doesn’t follow the fat tail VC valuation model like in the US and China, who have 260 and 204 Unicorns respectively, it does roll out many smaller companies with amazing products, on brand with its Mittelstand culture.

If you follow what founders and tech investors have to say however, you hear little complacency and a whole lot of complaints. The disappointment doesn’t lie in sheer numbers per se as much as the long term trajectory of how policy around Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOP) is shaping the fate of startup competitiveness.

Aside from funding constraints, more than half the startups point to hiring as a key challenge. In fact, German startups have on average five vacant positions at any given time, mostly attributable to a scarcity of skilled workers and their high salary expectations. More than one in four German startups also struggle to compete with larger, established competitors that can offer higher salaries and better non-financial compensation schemes. Employee Stock Option Plans help solve this problem. Stock options are typically the reason why top talent in engineering and business joins startups in the first place.

ESOP in a Nutshel

Internationally and in Germany, ESOPs come in different shapes and forms, but the overarching idea is that they allow cash strapped startups to give employees greater ownership interest in the company, either through direct stock kept in a separate trust account or through stock options [contracts that give employees the right but not the obligation to purchase stock at a fixed rate (strike price or exercise price)].

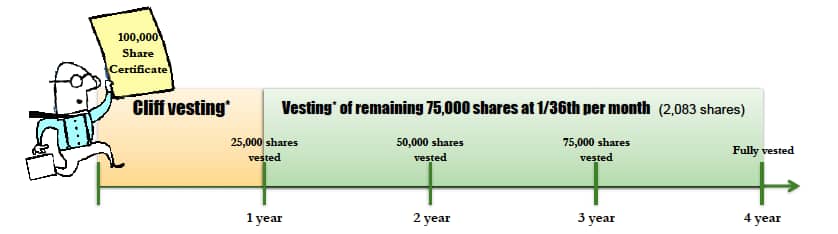

These stocks or stock options are prorated (vested), contingent upon the time spent with the company. In the typical example above, the startup is tying distributions from the plan to vesting – the proportion of shares earned for each year of service. If an employee was to leave before the cliff period (of 1 year), she wouldn’t receive any of the prorated shares.

As a founder, when you’re creating an Employee Stock Option Pool out of Restricted Stock, you have to pay attention to dilution. Will ESOP dilute founders only? Founders and Seed Investors? Founders, Seed Investors, and Series A Investors? An infamous case study by Naval gives some perspective on small details to look out for when you’re fundraising. Spoiler: a phrase as small as “fully diluted” will make all the difference in whether ESOP implied costs (from dilution) are carried together with investors or solely by the founding team.

Virtual Stock Option Plans (VSOP): The go-to choice for German Startups

Phantom Shares also called Virtual Stock Option Plans (VSOP) are more pragmatic in Germany and have been the go-to method by which most startups (> 80%) choose to give employees ownership interest. The reason why this model has become more prevalent over others has to do with the arcane German tax laws and shareholders’ standing in a GmbH. In Germany, receiving shares as a non-founder (not being a natural shareholder from the get go) can impose a major tax burden. If you are a founder, you own the shares at nominal valuation and the value of those shares grow over time. In case someone gives you shares in a company with a Fair Market Value (FMV) already established via a financing round for example, the German tax office treats it as taxable income, similar to a salary (Lohnsteuer). The receiver of those shares becomes taxable based on the valuation of those shares, ultimately paying tax on the difference between her strike price (low) and FMV (high). In German tax laws you are taxed when you are receiving value. Since a valuation of these shares has been established, you’re considered to have gotten something of value by receiving real shares.

Example: Founders establish a company together and put in the nominal value of EUR 1 per share. For simplicity, one founder owns 50.000 shares, having put up 50.000 EUR as share capital (Stammkapital). With a seed round of 400.000 EUR at a valuation of 2.000.000 EUR post money, the new shareholder gets 15.000 shares for 20% of the company. The value of the shares of the original founder have increased to roughly 1.300.000 EUR but she already had those shares. She didn’t receive anything, similar to stock price asset appreciation in the stock market. But if you then want to create another 13% in shares (10.000 shares) and give them to an employee, then those shares have a value far above 10.000 EUR, that person is getting all the value post money. To be exact, it’s over 260.000 EUR in value, something the employee has received through transfer. Hence, according to German tax law, that value needs to be taxed as income. Just imagine you are at a 100.000.000 EUR valuation and want to give your newly hired star developer 1%. She would need to tax 1.000.000 EUR, a cash position few people have, just to cover their tax obligations.

The Phantom Stock model gives a right to receive virtual shares that only materialise when the startup exits. At that moment shareholders commit a predefined amount of exit proceeds to those employees who took part in the ESOP Program. The employee then receives fiat currency in her bank account which is only taxable then. That way, she pays taxes only when her cash position allows her to do so.

The question is how to create a virtual share pool for employees. Like other ESOP models, this typically requires battalions of legal / tax advisors, but in theory the process entails a simple legal document signed by all shareholders in a shareholder resolution or directly in the shareholder agreement. All shareholders commit a certain part of the exit proceeds to be paid to those employees. Simply put, think of it as a few additional shares created at a certain date, fully dilutable like all the other shares, that come into existence at exit. Assume you had created a pool of 20.000 phantom shares when you had 90.000 shares, and then raised other rounds adding up to a total of 180.000 shares. At the time of exit all costs of the transaction as well as liquidation preferences will be paid out to investors, and instead of distributing the rest to 180.000 shares, you are distributing them as if 200.000 shares had existed. The 20.000 phantom shares are paid out as bonuses to employees. In effect, it counts as “virtual” shareholder dilution that applies to all shareholders.

ESOP Bundestag Reform

ESOP plays such a crucial role in startups that it’s become a key driver of country level startup friendliness indices. Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania were rated as the world’s most startup friendly countries thanks to favourable stock options schemes. Unfortunately, Germany ranks at the bottom of the list. Without the right tax policies, such as deferring tax burdens upon exercise, stock options can seem worthless to employees, unless the startup is nearing an exit.

Across Europe, entrepreneurs, investors and startup employees have been calling for reforms to stock option policies. One such campaign – Not Optional – is working towards better regulations for employee participation programs (ESOP) across Europe. The pan-European initiative is led by Index Ventures, a venture capital firm based in London, San Francisco and Geneva. In an open letter signed by 700 people involved in European startups, the campaigners wrote: “The next Google, Amazon or Netflix could well come from Europe, but for that to happen, reforming the rules of employee ownership is definitely not optional.” Many prominent founders such as Christian Reber from Pitch or Johannes Reck from GetYourGuide have also joined the demands. Christian Miele, partner at Headline and president of the German Startup Association, is also backing the initiative with the might of the lobby group. The German Startup Association has drummed up the initiative with its own #ESOPasap campaign for better employee participation programs in Germany.

Even after a major push in the Bundestag, which recently addressed some of the issues in a draft bill (Fondsstandortgesetz), the discrepancy between policies enacted and expected outcomes is still pretty wide. Nikolas Samios, author of dealterms.vc, criticised crucial points in a Gründerszene op-ed. Christian Miele is also calling for improvements: “With the current draft that is now available, we cannot play in the league of startup nations.”

To delve deeper into ESOP critique and how the new draft law falls short in more detail, a statement by law firm SMP covers it pretty well. Their bottom line: “In light of the shortcomings of the draft bill, we cannot currently recommend offering new employee stock ownership plans or converting existing programs accordingly. Market standard exit or IPO-related option programs or virtual programs (as discussed in the VSOP example) remain the more favourable option for the time being. We remain hopeful that the draft bill will be revised during the legislative procedure, taking these aspects into account.”

For questions about the program and our curriculum, please contact [email protected]

This program is financed by the European Social Fund (ESF), as well as the State of Berlin.