Not knowing who to sell your product or service to can cost you a lot of time, money and pulled-out hair. Understanding your customer (user/client) is not only crucial for sales. Insights about who your early adopters and soon to be raving fans are also play into product/service design and expansion, financial modeling and overall business growth. So…

Why is Customer Discovery often done half-heartedly by early entrepreneurs?

I believe there are a few different reasons:

- There is no immediate ROI. Going through your competitors’ followers on Facebook trying to find patterns doesn’t directly lead to sales. As a result, manual research activities like that often end up at the bottom of the to-do list.

- It is pretty scary. Approaching random people at the park, asking them to use your product and give you feedback means putting yourself out there and being vulnerable. For starters it is super awkward if you aren’t a born extrovert. And then it can be nerve-wrecking watching people taking apart and criticising something you poured your heart into.

- There aren’t so many great resources available on how to structure the process of Customer Discovery and actually do it. I really appreciate Steve Blank’s (here is a free Udacity course on his methodology “How to Build a Startup”) and Eric Ries’s work on the Lean Startup, which lead to a push towards Customer Discovery and Validation. Rob Fitzpatrick’s The Mom Test also provides real gems about how to ask questions and really understand whether there is a need for your solution or not. But I haven’t seen a resource showing entrepreneurs how to hypothesise, collect and analyse the data necessary for Customer Development.

To combat the above notions and gaps, the second big workshop at the High-Tech SeedLab focused on Customer Development. The goal was to develop a clear process of Customer Discovery to eventually find and prove product-market fit.

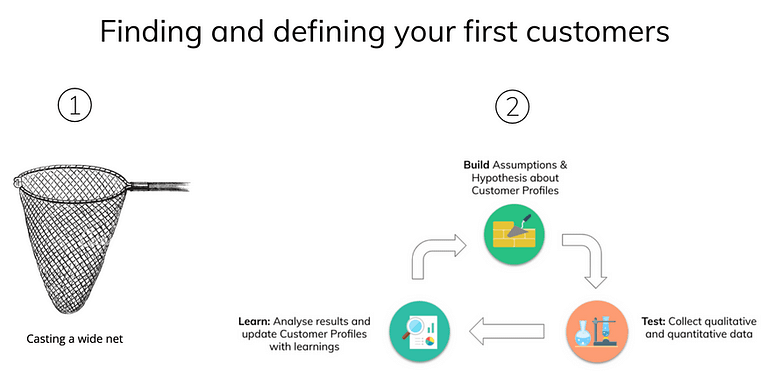

There are two ways to go about finding the people that would part from their hard-earned money to receive your product or service. Either you cast a wide net and see who gets caught, or you take the “scientific” route of Build-Test-Learn. While the safest way is to engage in both activities, the second one requires a deep-dive. So we set out to identify a roadmap for developing a customer-centric, scientific process that puts evidence behind an assumed product-market fit.

And of course, we are happy to share.

1. Build hypothesis about your product-market fit

When you started your venture, you probably had specific customer segments in mind. While you might be right, it is often the case that you’re not. What happens when you’re wrong? This:

The first step, therefore, is to admit to yourself that you need to test your assumptions. Then, you can go through them and test them one by one.

Start with your assumptions about potential customers

So let’s get started by laying out your assumptions in front of you:

Demographics: gender, age, income, family, (company) location

Background: job title, career path, job responsibilities, decision-making power, industry (for B2B: once you brainstormed relevant job titles it might be useful to do some LinkedIn research and see what kind of tasks/achievements people with these job titles mention on their profiles)

Psychographic description (what do they like/don’t like, what do they do/don’t do, what are their priorities and concerns, what are they scared or worried about, what are their motivation to use your product/service?)

What are functional/emotional/social jobs? → Main needs and problems (what problems are they facing/wanting to be solved?)

Current ways of solving the problem (Are they currently buying a different solution? What are they doing currently to solve the problem?)

Usage Behaviour (how often do they need your product or a product like yours? What retailers/brands do they usually prefer? What is their estimated customer lifetime value?)

Price sensitivity (Pretty self-explanatory)

Channels and accessibility (which marketing channels do they usually use? Where do they buy their current solutions? What similar products do they buy and how?)

Then, look where there are similarities and differences in people’s characteristics and behaviours. Use the differences to define clear segments. To understand who you need to focus on in your testing, you can then use the SPA treatment to prioritize possible customer segments.

Then develop value propositions for each customer segment

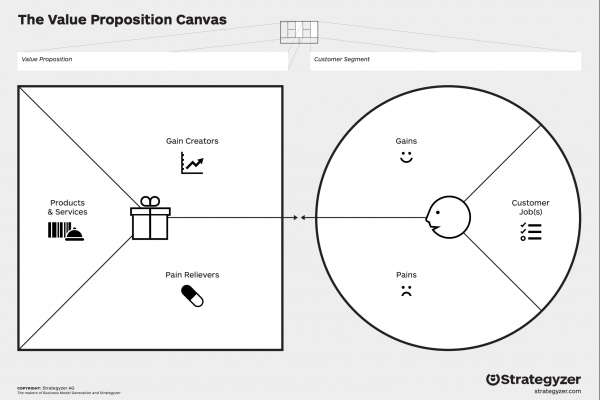

Once you have your winner, you need to dig deeper into your value proposition. How does your solution help this specific customer segment to get their (emotional/ social/ functional) job done? What gains are you providing? What pains are you eliminating?

If you are familiar with the business model canvas and Alexander Osterwalder, you’ve probably realised that the Value Proposition Designer Canvas is a great tool to map the functions and benefits of your solution to a specific customer segment.

In the end you want a statement that clearly defines your Customer- Segment- specific- Value- Proposition (CSVP). And yes, we came up with that abbreviation ourselves.

2. Test your assumptions by collecting qualitative and quantitative data

Phew, that was already quite a lot of (hypothetical) work. Now it’s time to “get outside the building” (huge Steve Blank fan over here) and test if you were right.

And to be completely honest – this is the hardest part. Reaching potential customers is tough. And often it is non-scalable. One of the recent gems that were shared by one of our participants is an article by Lenny Rachitsky on how the biggest consumer apps got their first 1000 users. Unfortunately, it was not Facebook Ads (even though they might still present a worthy try).

Here are a few of the ideas we have come up with:

Guerilla marketing and interviewing

Speaking to your first few customers if you have any

Checking your Google Analytics account if you’ve created first traction to your website

Cold emailing/LinkedIn-ing (especially B2B) and asking them how they are currently solving the specific problem (and if they have it)

Online research of forums and reviews of competitor products

Paid ads and landing pages

Stalking of followers of competitor products online and on social media

Handing out free samples/trials and watch people’s reactions

Find potential customer segments in their natural habitat and infiltrate them (groups, MeetUps, Associations etc.)

So there is loads of qualitative and quantitative data waiting to be collected. To not get confused and be a little more structured, I would advise organising smaller experiments that focus on one or two of these outreach ideas. This means clearly defining your hypothesis and how you want to test it.

3. Analyse your data to flesh out customer personas

You are now left with a bunch of data from interviews, website insights and customer feedback. What do you do with that?

You compare your hypothesis to the insights provided by your experiments and see if your assumptions were true or not. And then? This is where it gets fluffy. Before completely throwing an assumption out the window because one person said something contradictory, you might want to design another experiment to see if there is a general consensus on the contradiction. And vice versa.

I recently listened to an interesting podcast on foundr where Alex Osterwalder said something about testing business models being “a science and an art” at the same time. The process we just laid out is the science part. The art is to then decide when something is confirmed or rejected. So unfortunately, there is no clear answer. But as a rule of thumb, stopping when you hear the same thing over and over again might be helpful.

Please stop reading now and start your own customer discovery process.

You think you have a great product-market fit but need time and support to test your assumptions? Applications for the 2021 batch of the High-Tech SeedLab open in October. Email [email protected] to find out more.